On 21st March every year, Australia celebrates Harmony Day. School children all over Australia celebrate by wearing orange and learning about their classmates cultures and highlight the ‘harmonious’ nature of our society with the tagline ‘Everyone Belongs’.

The history of this day, however, is a little more complicated.

In the rest of the world, 21st March is the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. It was announced in 1966 by the UN General Assembly in response to the Sharpesville Massacre , where, in 1960, South African police killed 69 peaceful demonstrators who were marching against apartheid.

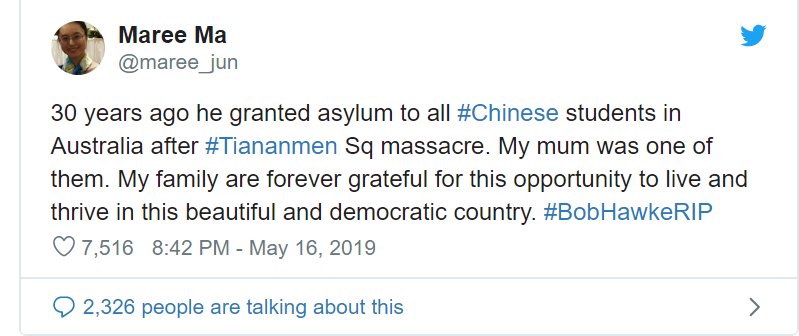

In 1998, the Howard government commissioned research into the Australian public’s view of racism, with the view to use this research to release an educational and media ‘anti-racism’ campaign. The campaign would have to encompass the Coalition’s concept of Australia as ‘a country whose people are united by the common cause and commitment to Australia’ in a climate of anti-immigrant stories in the media about immigrant gangs and fear mongering from Pauline Hanson that “we are in danger of being swamped by Asians”.

What this extensive Eureka Research report found was deemed too dangerous to release to the Australian people until the Freedom of Information fifteen years later.

Remembering that the research took place before 9/11 when the media was targeting Asian communities as the biggest danger, the report found that 30% of people thought Asian migrants were taking jobs and 40% of people thought that Asian migrants were heavily into crime and drugs. Two in five respondents could see “why some people are racist towards them (migrants and Indigenous people)”.

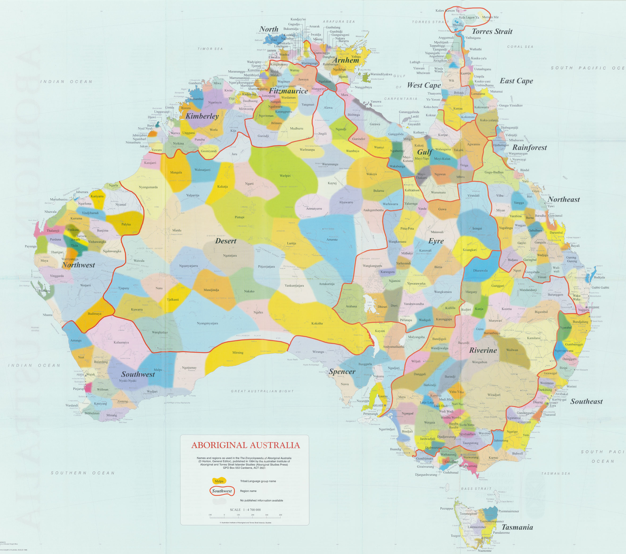

As regards Indigenous people, the report found that a quarter of the respondents were unable to come up with any positive contribution that Indigenous people have made to Australian society.

The research showed a clear need for an anti-racism campaign in Australia. The difficulty became what people believe racism is.

There are two types of thinking about this, those that believed racism to extreme and involved violence or direct discrimination and those that believed racism to be more widespread and multi faceted.

Those that believed racism to be extreme did not regard themselves as racists though they were found to have racist ideals.

Six statements were put forward as values that were recognisably Australian.

The statements that were agreed were recognisably Australian were ‘helping one another in a crisis’, ‘a fair go’, and ‘a desire for community harmony.

The statements that the respondents did not agree were recognisably Australian were ‘equality’, ‘acceptance of others’ and ‘tolerance’.

The Howard government stressed that ‘anti-racism’ was not be discussed in the campaign and that ‘a desire for community harmony’ should be highlighted.

The Harmony Day campaign was released to show how harmonious Australia already is and to stress how fragile and precious that harmony is. The responsibility was placed on the diverse migrant communities to assimilate to Australia’s way of life and values to protect that harmony.

The attitude we can see that stems from campaigns such as this that permeate Australian culture is that any criticism made of migrant communities failure to assimilate is not racist, rather it is an attempt to protect the harmony that Australian society is striving for.

This is perfectly summed up by Pauline Hanson in 2016:

“Tolerance has to be shown by those who come to this country for a new way of life. If you are not prepared to become Australian and give this country your undivided loyalty, obey our laws, respect our culture and way of life, then I suggest you go back where you came from.”